About Chinook Salmon

Oregon Coast Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are an essential part of the ecology, culture, and economy of the Pacific Northwest.

Typically, the largest-bodied and more nutritious of the five species of Pacific salmon, yet the least abundant, you could say Chinook—also called King salmon—play an outsized role in supporting Oregon’s coastal food webs. Seabirds, sharks, sea lions, seals, otters, raptors, bears, and wolves all depend on salmon as part of their diet. Chinook Salmon are the primary prey for the endangered Southern Resident orca whale population. When terrestrial predators carry adult salmon carcasses inland from streambanks to eat, marine-derived nutrients enter the terrestrial system, fertilizing the forest. And salmon remains that decay in-stream feed the base of the food chain by nourishing aquatic macroinvertebrates.

Since time immemorial, indigenous peoples of the Northwest have incorporated salmon into their subsistence practices and worldviews. As canning and other processing technologies emerged, newer arrivals to the region sought salmon for commercial aims. By 2015, the Oregon commercial salmon fishing industry generated $18.2 million in total personal income. Sports fisheries are also well established, and angler dollars further support local economies. In 2015, the Research Group estimated the total economic contribution for Oregon’s non-Columbia River coastal inland estuary and freshwater recreational salmon fisheries at $37.54 million for the 2013 and 2014 seasons.

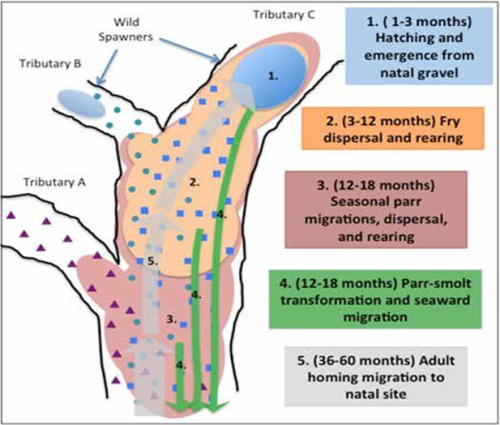

Adult female salmon lay their eggs in nests they build—called redds—in the gravel streambeds. Redds create prime temperature and oxygen conditions for fertilized eggs to develop by allowing for optimum flow-through of water. After the eggs hatch, they retain their yolk sac in what is called the alevin stage of their life and use its’ remaining nutrients until their mouth develops and they can eat small aquatic macroinvertebrates on their own. At this point, they are called parr, due to oval marks on their sides that help them camouflage in the gravel.

Different species of Pacific salmon will reside in freshwater from anywhere between a week and a couple years. During this time, they imprint on their natal stream using olfactory cues from its' environment.

If the parr survive, they move onto their next life stage in the mixed salt and freshwater environments of estuaries. Here they undergo a metabolically expensive process called smoltification, in which their physiology changes so that they can survive in saltwater.

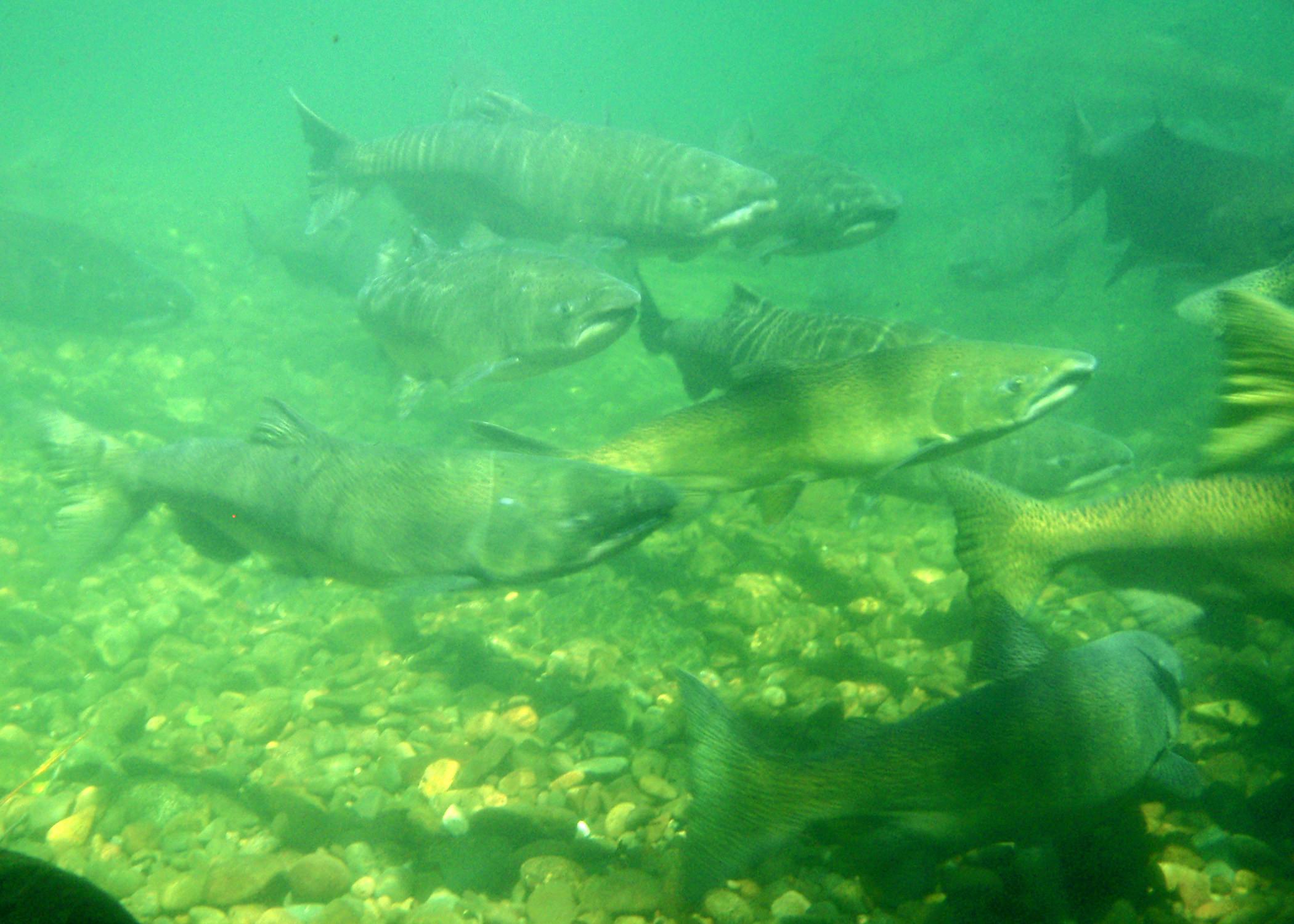

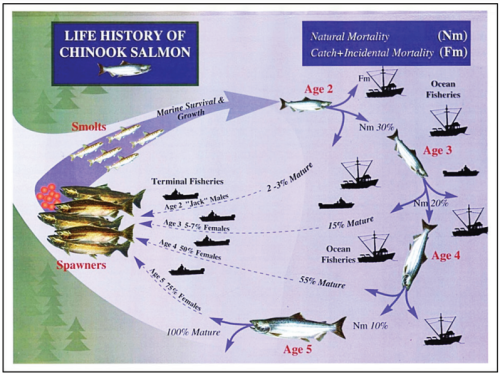

Pacific salmon spend 1-5 years in the ocean depending on the species. When they are reproductively mature, Pacific salmon return, or "home" to their natal streams to spawn. When they enter freshwater, they cease eating and focus all their time and energy on moving upstream.

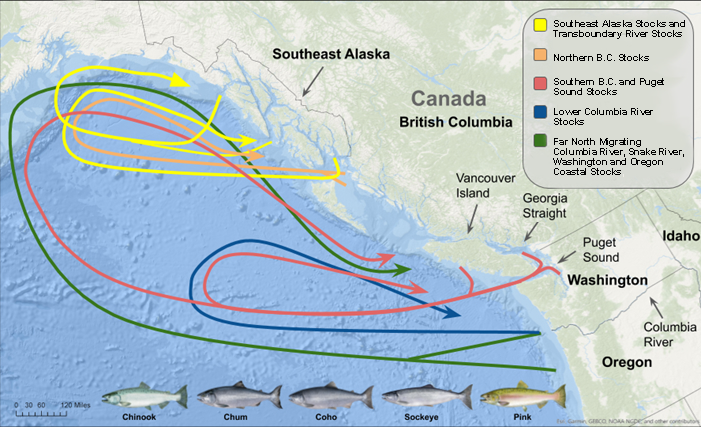

Chinook Salmon’s migratory life history exposes them to a wide range of threats. Early life stages are vulnerable to scouring flow events, predation, and sedimentation. Juveniles and smolts are frequent prey of larger fish, marine mammals, and birds during their migration through river and estuary to the ocean. Once in the Pacific Ocean, Chinook Salmon from many of Oregon’s coastal rivers and streams travel north to feed and grow off the coasts of Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska.

While feeding in the marine environment, these fish are susceptible to intensive harvest by commercial and sport fishers, particularly in the waters off Alaska and British Columbia. The Pacific Salmon Treaty (PST) forms the principal framework that regulates harvest management for all Pacific salmon stocks of common interest to the U.S. and Canada. To effectively manage harvest of Oregon’s coastal Chinook Salmon stocks and respond to population downturns within local and international management regimes, accurate and precise measures of spawning adults and in-river harvests are required.

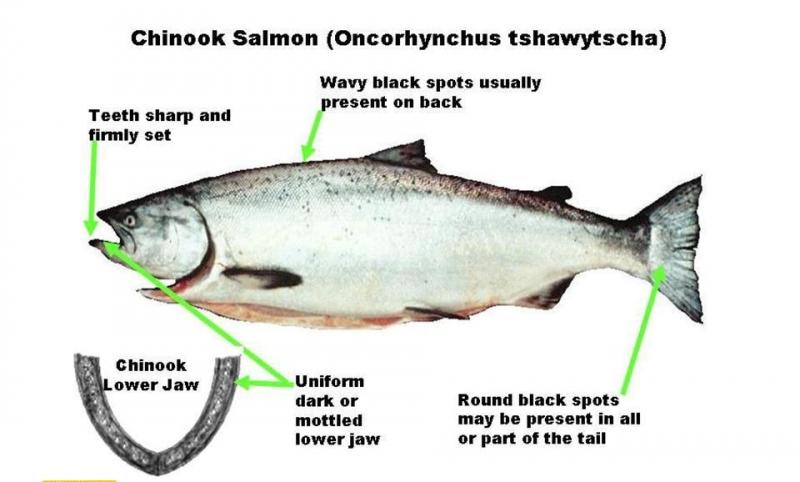

At first glance, Pacific salmon species may be difficult to tell apart. In the ocean, all salmon have a slightly darker hue to their backs with silvery sides and light bellies to camouflage from predators. However, each species has different coloration in their mouths and spotting patterns. And as adult salmon return to rivers to spawn, the coloration on their bodies changes. When fishing for salmon in the ocean, bays, or rivers, it is necessary to be able to identify each species, as some may be open for harvest and others not. Always know both the permanent regulations and in-season changes for your specific location before you go fishing. Check current regulations here: https://myodfw.com/articles/oregon-fishing-hunting-regulations-and-updates.

Chinook Salmon

Key identification characteristics for Chinook Salmon are their black mouths and gumlines, and large irregularly shaped spots on their back and both lobes of their tail fins. When they return to freshwater to spawn in the spring-fall, Chinook darken/green in color and may develop a degree of pink-red on their bellies.

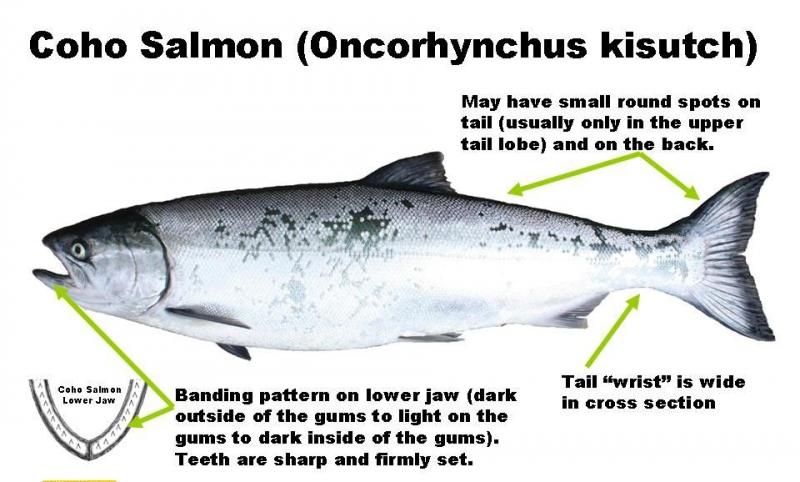

Coho Salmon

When misidentifications occur while fishing, it is most often that a Coho Salmon is mistaken for a Chinook Salmon. In contrast to Chinook, Coho have a white gumline in a black mouth, giving a black-white-black or “oreo” pattern. Coho Salmon have smaller, more regularly round shaped spots on their back and on just the upper lob of their tail fins. When they return to freshwater to spawn in the fall, Coho darken in color and develop brighter red on their bellies/sides. Generally, Coho Salmon do not reach the larger size of Chinook Salmon.

Oregon Coast Coho Salmon are an ESA-listed species, and often are not permitted for harvest except in high run years. Work is being done to restore Coho populations and their habitat across the coast by ODFW Fish Districts and their partners.

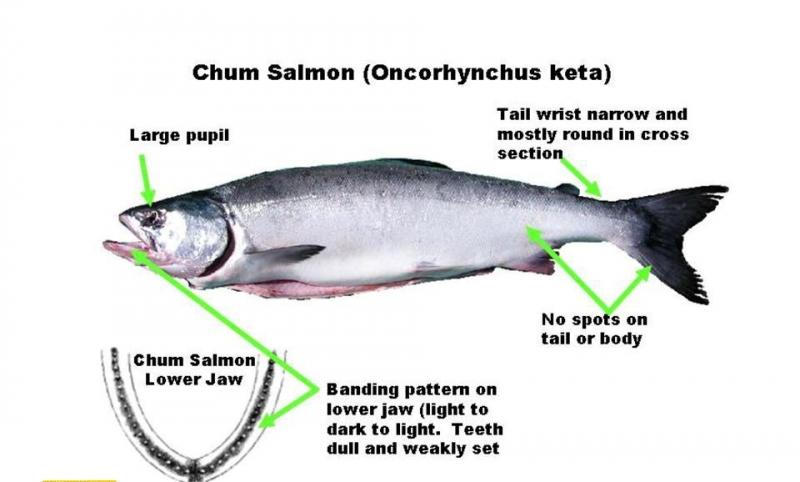

Chum Salmon

Chum Salmon have no spots on any part of their body. The coloring in their mouth is white-black-white. When they return to freshwater to spawn in the fall, they become dark green-brown with vertical purple marks on their sides.

Columbia River Chum Salmon are an ESA-listed species. Work is being done to restore this and other coastal populations by ODFW's Program to Restore Oregon's Chum Salmon and their partners. Note that Oregon's coastal rivers are closed to angling for chum.

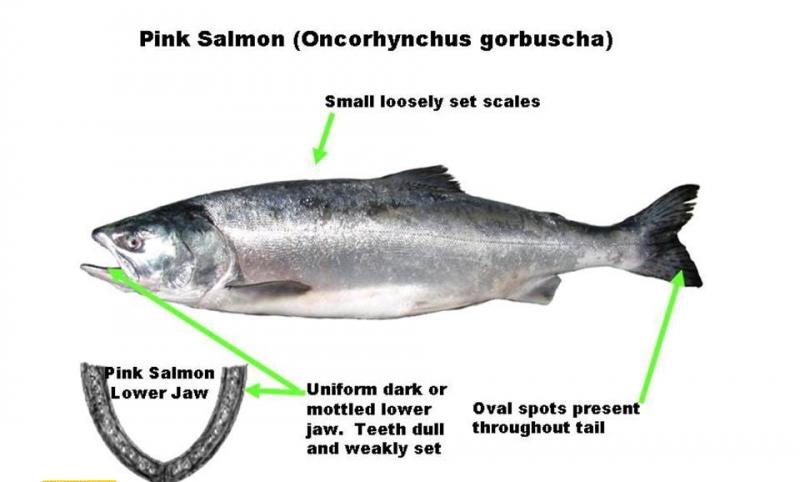

Pink

Pink Salmon have very large, irregularly shaped black spots on their backs, and heavy oval shaped black blotches on both lobes of their tails. They have a white mouth with a black gum line and tongue. When they return to freshwater to spawn in the fall, they become greener on their backs and whitish on their bellies. Males develop a hump on their backs earning this species the common name humpback salmon.

Pink Salmon are rarely seen in Oregon, as they have been extirpated south of the Columbia River basin. However, Pink Salmon are known to stray from their natal streams and sometimes are caught.

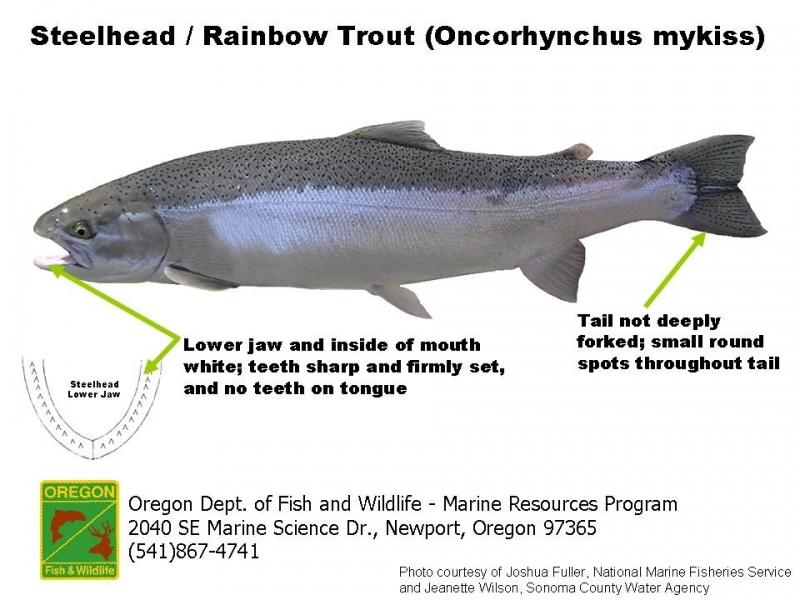

Steelhead

Steelhead are the ocean-going, or anadromous, form of Rainbow Trout. They have an entirely white mouth and small round spots on their back and both lobes of their tail. When they return to freshwater to spawn in summer-winter, their backs become slightly more olive green, and they develop pink along their sides and cheeks. Their body form maintains a more oblong shape than other returning Pacific salmon.

Steelhead are diadromous, meaning that they may complete two ocean to spawning cycles. This is unlike any other Pacific salmon, which only complete one cycle before dying.